Combat experience, cultural skills and COVID-19

Topics

Featured

Share online

Tim Stackhouse is a 21-year member of the Canadian Armed Forces. A master warrant officer, he’s the company sergeant-major for 1 Field Ambulance’s Medical Company, stationed in Edmonton.

Onekanew (Chief) Sinclair is head of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation (OCN) near The Pas, in northern Manitoba. He served in the Canadian Armed Forces from 1988 to ’95, doing tours of duty in Cyprus and Somalia. He was an infantryman, paratrooper, commando and, in the latter deployment, a sniper.

Why they met is COVID-19. The way they came together, however, is the story.

And it’s a story of culture meeting culture with mutual respect and common purpose.

Covid-19 outbreak

On Nov. 13, 2020, a COVID-19 outbreak was detected at the Rod McGillivary Care Home on the Opaskwayak Cree Nation. Every one of the facility’s 27 elderly residents was infected along with many of its 70-plus staff members.

Onekanew mena Onuschekewuk — the Opaskwayak chief and council — and OCN’s health authority quickly reached out to the federal government for help and, by Nov. 18, soldiers from CFB Shilo in southern Manitoba were on site, assessing needs. A few days later, Stackhouse and the 1 Field Ambulance crew, supplemented by three nurses, who are members of the military’s High Readiness Detachment and also work in civilian hospitals in the Edmonton area, rolled in.

Team members have paramedic training as well as specialized training in combat medicine. Stackhouse, a native of Saint John, NB, served in Afghanistan, providing medical coverage to combat teams and working at an international major trauma centre; he was also part of a medical team that responded to the 2015 floods in Portage la Prairie, Man.

But as much as Stackhouse’s combat medicine experience came in handy at OCN, so did his recent education at Royal Roads University. A student working remotely on a Master of Arts in Disaster and Emergency Management (he’s aiming to graduate in spring 2021), he had taken a course in intercultural competence with Assoc. Prof. Jean Slick.

When he learned of his team’s impending deployment to OCN, he reviewed the course material, paying special attention to “cultural icebergs,” which he explains this way: The top of the iceberg is what people show to others while the larger part below water is what others don’t generally know and what is sacred. In the case of Indigenous Peoples, the latter includes the importance of, and reverence for, Elders.

The first step was to focus on that first step on to OCN land, which is home to about 3,400 of the 6,300 Opaskwayak people. Stackhouse and company brought a gift — a 1 Field Ambulance Commanding Officer’s Pennant — to thank OCN leaders for welcoming them.

But the outreach didn’t end there. Stackhouse would meet daily with representatives of Opaskwayak Health Authority, and they would begin and end every meeting with a prayer.

As well, he says, “I made it my own personal goal to try to learn a word in Cree every day.”

“Tansi” is a greeting while “Tapwakiche” means “thank you” and “Ka wapamekawenawow” is not goodbye but, rather, “We shall see you.”

“So by day three, when I walked in and greeted them in Cree, they lit up… By day four, I was saying ‘How are you?’ That added to the trust, it added to the connection that we’re here to help and we’re on the same team.”

“We appreciated that and we recognized that,” says Marie Jebb, a nurse manager with the Opaskwayak Health Authority. “And I think those are the kind of touching gestures that communities really appreciate and acknowledge. They see that there is a concentrated effort being made to make sure that you are learning the culture of the people.”

Onekanew Sinclair agrees, saying that despite a history that includes conflict between Canada’s First Nations and its military — he cites the Oka crisis in 1990 as a particularly bitter example — and because of a history of service in the armed forces by Indigenous people, there was mutual respect between the Opaskwayak and the visiting military personnel.

Brushing hair, intimate care

But while words were powerful, so were the deeds of Stackhouse and company in caring for sick OCN Elders.

“These are guys who spent a few years in a training system where they’re learning to save lives while there’s gunfire around them,” he says of his colleagues.

At OCN, however, they were providing one-on-one care to Elders that went beyond medicine, with 1 Field Ambulance members helping residents wash, bathe and go to the bathroom. One of Stackhouse’s colleagues asked a care aid to show them how to brush someone’s hair, others learned to cut hair or help the men shave.

“It was humbling for our crew to get that opportunity,” he says. “It’s not combat medicine anymore.”

“I think that’s important,” says Jebb. “You see there is a genuine respect and acknowledgement of the Elders and the community. And our Elders are held in very high esteem and we believe that we need to look after them and provide the comfort they need.”

A special ceremony

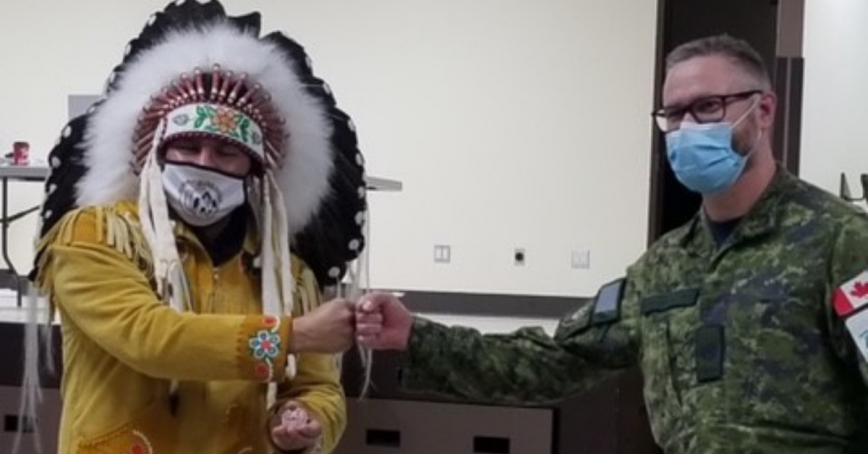

Nowhere was that mutual respect more evident than at the end of the seven-day OCN deployment.

Onekanew Sinclair and Opaskwayak leaders invited Stackhouse and the 1 Field Ambulance crew to a smudging ceremony. Noting that the Cree have been practising smudging for millennia, the Chief explains the ceremony’s purpose is to purify the senses and get rid of negative thoughts and energy.

The entire team lined up to participate, Stackhouse says.

“Everyone embraced it. You could see it on their faces. It was as spiritual regardless of who you are and where you say your prayers and who you say your prayers to. You could feel it. You could sense the peacefulness in the room.”

Now, just as Stackhouse took his university course work into the field at OCN, he has since taken his team’s experience with the Opaskwayak ininew (people) to work with other First Nations.

And his goal is to carry all of those experiences with him in his future in the Canadian Armed Forces and beyond.