Beyond policy: What makes health-care workers feel safe on the job?

Learn more about the Master of Business Administration program.

The baseline of health care should be safety. Yet for many workers, the biggest threat is not an accident with equipment, it is violence. From patients or visitors lashing out in fear, pain or frustration, aggression has become a routine job risk.

Research shows the toll of injuries, stress, burnout and lasting trauma is mounting. Equity-deserving employees are often targeted more often, and the consequences can be more severe.

Hospitals and health authorities have responded with de-escalation training, new procedures and updated policies. But a critical question remains: do these measures make employees feel safer?

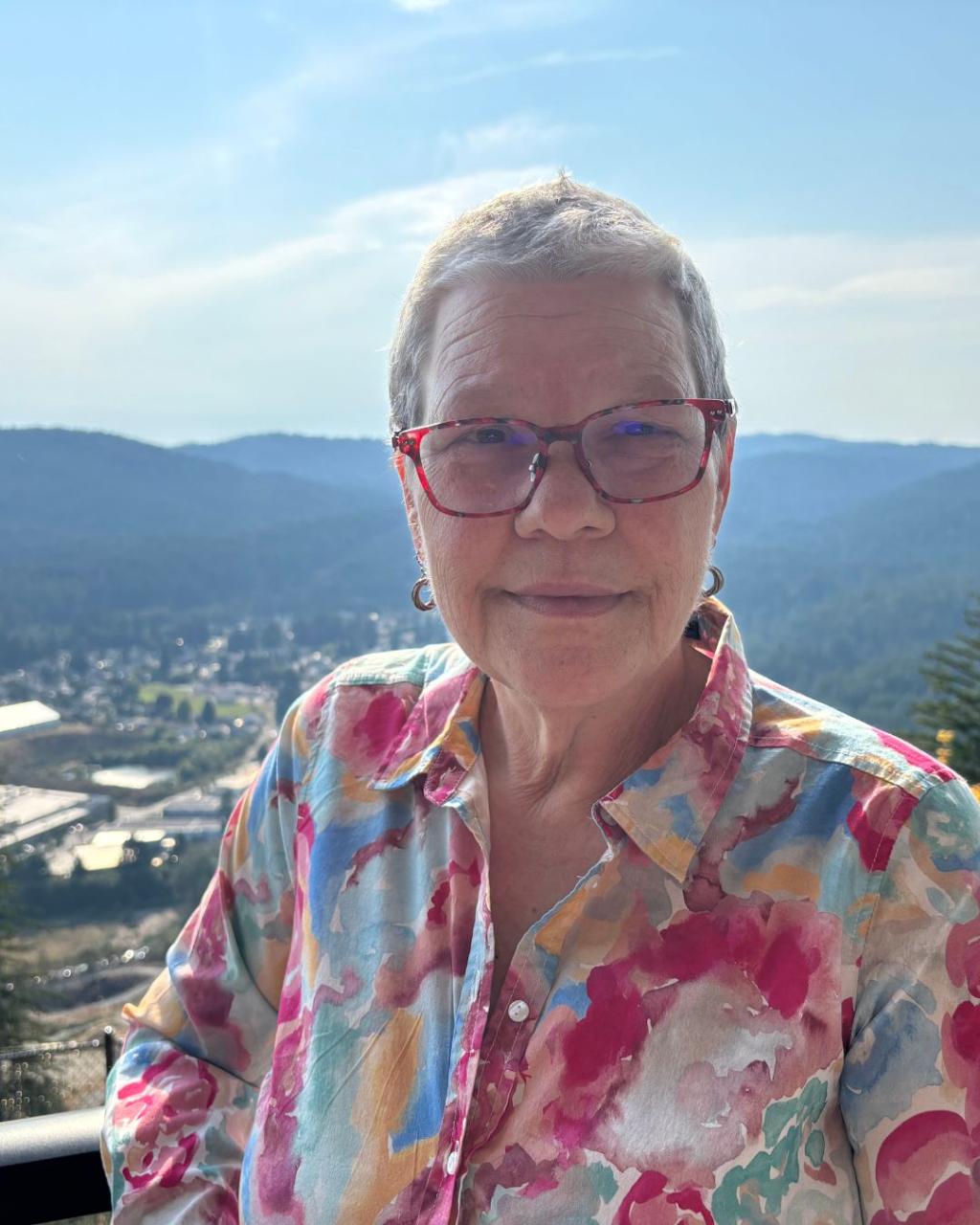

Frances Jorgensen, professor in the Master of Business Administration program at Royal Roads University, in collaboration with Island Health, is leading a study that asks health-care workers directly about their perceptions of safety interventions.

“Most of my career has been looking at employee perceptions and how they respond to management,” Jorgensen says. “With my workplace inclusivity research, I realized we weren’t going to stop people from being rude, but what we could do is try to intervene. So, my focus has shifted almost entirely to studying interventions.”

Jorgensen and her team conducted qualitative interviews with 63 employees including nurses, protection services officers, housekeepers and other staff who work face-to-face with patients and the public in acute-care departments across Vancouver Island.

While managers had introduced multiple safety initiatives in the past year, only 23 per cent of staff interviewed said they were aware of them and an overwhelming majority, more than 90 per cent, reported the measures did not increase their sense of safety at work. Employees who felt they could confide in their manager after an incident felt safer, but interviewees also voiced frustration about being left out of the process of developing interventions.

“They were surprised they had not been asked and involved in determining what those types of interventions should be,” Jorgensen explains. Even simple measures, such as a buddy system, could have helped staff feel safer, but they weren’t asked.

“This is kind of a dilemma in management,” she adds. “We have so many employees, we cannot go and talk to every single one. And sometimes we have to make decisions quickly. But if they can give employees the sense that they are valued through asking their opinions, that makes a world of difference.”

The findings suggest that while interventions may exist on paper, their success depends on how staff understand and experience them. The research offers practical insights for how policies can be designed and communicated to better support staff safety. A summary report will be shared with Island Health so leaders can use the results to inform future initiatives.

“Shining the light on the employees, to a degree that maybe hasn’t been recognized before, that’s the most rewarding part of this research,” Jorgensen says. She will present the findings at the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology conference in New Orleans in 2026, where she hopes to spark international collaboration and add to the growing body of research on organizational safety interventions.

Learn more about the Master of Business Administration program.