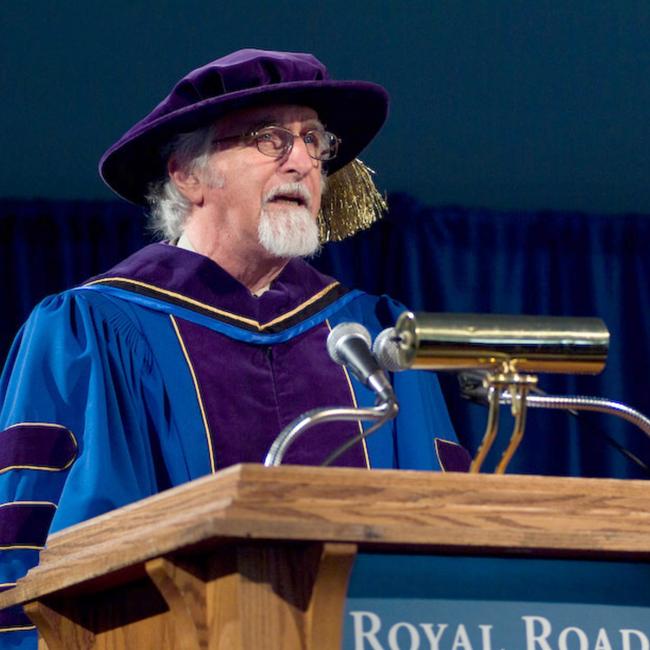

Gary Geddes

Honorary Degree

Spring 2007 Convocation

For nearly 30 years, Gary Geddes has been one of Canada's most influential political poets, advocating justice and human rights through his prose.

Gary Geddes was born in Vancouver, B.C. in 1940. Before taking up writing, travelling and academia, Mr. Geddes was as a gillnet fisherman, a water-taxi driver, and a worker at the B.C. Sugar Refinery. He went on to earn degrees in English and philosophy at the University of British Columbia, and his MA and PhD in English at the University of Toronto.

Geddes has taught English at Concordia University, the British Columbia Institute of Technology, and the University of Victoria. In September 1998, he was appointed as the Distinguished Professor of Canadian Culture at Western Washington University. He has had numerous appointments as writer in residence, including at the University of Alberta, Malaspina University College, University of Ottawa, and Green College at UBC.

Geddes has performed and lectured extensively around the world. He has published and edited more than 35 books of poetry, fiction, drama, non-fiction, criticism, translation and anthologies, along with launching several publishing companies. The National Library in Ottawa houses his archives. Among dozens of national and international awards, Geddes can claim the Americas Best Book Award and the Gabriela Mistral Prize.

Most recently Geddes authored The Kingdom of Ten Thousand Things, non-fiction misadventure that finds him following the journey of a fifth-century monk across Asia and the Pacific, from war-torn Afghanistan to Guatemala. His book-length poem Falsework, based on the 1958 tragedy at Second Narrows Bridge in Vancouver, is due out this year.

Geddes performed a reading from The Kingdom of Ten Thousand Things at Royal Roads University in 2006 for "Blueprint for Peace," a fundraiser for the Human Security and Peacebuilding program's Uganda residency.

Speech by Gary Geddes

A love-letter from French Beach

Mr. President, Mr Chancellor, illustrious faculty, distinguished guests, graduating students, ladies and gentlemen, I'm honoured to be in your presence today and to accept this degree. As I pondered this wondrous invitation into your midst, feeling unworthy and wondering if it was all a mistake, I couldn't help recalling that famous remark of Harpo Marx: "I wouldn't want to join a club that would admit the likes of me." Seriously, thank you for this gracious gesture and the moral support it embodies

In 1987, I had the opportunity to interview human rights workers, victims of the coup in Chile, and Jaime Hallas, publisher of the Chilean magazine Análisis, which had been closed down repeatedly by the military. These were difficult times. The regime had squandered its reserves of moral indignation and had no easy excuse for carrying on its deadly games; American support was slipping; and an attempt had been made to assassinate Pinochet. The proverbial sticks and stones of the opponents had proven inadequate to oust the General; all that remained were the names, or words, that are not supposed to hurt, but which were gaining ground in the struggle to sway international opinion and rally domestic support.

Hallas was a tall bearded man. He was seated in the make-shift offices in front of a poster-sized photograph of his foreign affairs editor, who had been murdered by Pinochet's thugs months earlier. Hallas was trying to explain to me Chile's unusual censorship laws, which did not exactly ban books, but which managed to keep a strong lid on dissent just the same. "Here your books may survive," Hallas said, running the fingers of one hand through his thick beard, "but you may not." As he spoke, I thought of the Chilean musician Victor Jara lying dead in the stadium with his hands smashed for daring to stir the prisoners to song; I thought of Pablo Neruda, fleeing through the Cordilleras to Argentina years earlier as the copies of his Canto General were clandestinely printed and distributed in Santiago; and I thought of my Chilean friends Nain Nomez and Leandro Urbina, two contemporary exiles from the terror living and trying to write in Canada.

I apologize for mentioning this sobering event on such a festive occasion, but it reminded me of how much we take for granted those freedoms which our forebears in this country struggled so hard to win. One of the most important of these is the freedom to imagine, freedom to imagine the Other, to imagine a better future for ourselves, for our country and for the peoples of the world, freedom to imagine the unconventional and to construct a vision that goes against the grain, that stands tall in the face of opposition.

For me, that is what poetry is all about: a verdict, a call to arms, a message from the heart, an urgent final communication. Nobel laureate Octavo Paz has insisted that "a society without poetry is a society without dreams." Here's a folksy example of how poetry works on a simple domestic level.

At five years of age, my grandson Jeremy, never an enthusiastic eater, was at the supper-table playing with his food, using his thumb to forge a channel through his mashed potatoes along which the river of rich, brown gravy could run, when his mother's friend Cameron, in exasperation, said: "Jeremy you're really weird." Jeremy looked quite puzzled for a moment, not quite knowing how to process this information. Then he looked up at Cameron and said: "Sometimes I'm weird, sometimes I'm not." This little piece of word-music, this symmetrical structure, pleased him so much he could be heard throughout the evening expanding his repertoire: "Sometimes I'm lucky, sometimes I'm not; sometimes I'm purple, sometimes I'm green." He had created a lovely verbal construct, a repetitive rhythmical apparatus to help him ward off adult aggression; in other words, he'd struck a blow on behalf of personal freedom, he was using poetic techniques to shape and control his world.

Watch out when a poet puts the right words in the right order because, according to former US laureate Robert Hass, "rhythm has direct access to the unconscious, . . . it can hypnotize us, enter our bodies and make us move, it is a power. And power is political."

During the Vietnam War, when the Ohio National Guard opened fire on the unarmed students at Kent State University, killing four and wounding nine others. I found myself in a state of great agitation. I could make no sense of what was happening; my grief and rage demanded some sort of poetic resolution, some shape that would give these events personal meaning. I tried without success for six years to write a poem that would put to rest these demons. Then one day I walked into a second-hand bookstore in Edmonton and found a small red paperback called The Killings at Kent State by the great American journalist I.F. Stone. Stone tried to understand why no members of the military had ever been brought to trial for these killings. As I walked home with this little red book, which cost me a dollar, I noticed four details that galvanized my attention about one of the victims, a girl named Sandra Lee Scheuer: she was a speech therapy student, she was very tidy, she loved to roller-skate, and she knew nothing about politics. Somehow the time was right and the necessary materials were at hand, so I chucked my previous efforts and sat down to write. This is what came to me.

Sandra Lee Scheuer

(Killed at Kent State University on May 4, 1970

by the Ohio National Guard)

You might have met her on a Saturday night

cutting precise circles, clockwise, at the Moon-Glo

Roller Rink, or walking with quick step

between the campus and a green two-storey house,

where the room was always tidy, the bed made,

the books in confraternity on the shelves.

She did not throw stones, major in philosophy

or set fire to buildings, though acquaintances say

she hated war, had heard of Cambodia.

In truth she wore a modicum of make-up, a brassiere,

and could, no doubt, more easily have married a guardsman

than cursed or put a flower in his rifle barrel.

While the armouries burned she studied,

bent low over notes, speech therapy books, pages

open at sections on impairment, physiology.

And while they milled and shouted on the commons

she helped a boy named Billy with his lisp, saying

Hiss, billy, like a snake. That's it, SSSSSSSS,

tongue well up and back behind your teeth.

Now buzz, Billy, like a bee. Feel the air

vibrating in my windpipe as I breathe?

As she walked in sunlight through the parking-lot

at noon, feeling the world a passing lovely place,

a young guardsman, who had his sights on her,

was going down on one knee as if he might propose.

His declaration, unmistakable, articulate,

flowered within her, passed through her neck,

severed her trachea, taking her breath away.

Now who will burn the midnight oil for Billy,

ensure the perilous freedom of his speech?

And who will see her skating at the Moon-Glo

Roller Rink, the eight small wooden wheels

making their countless revolutions on the floor?

If there is one more urgent final communication I can share with you as you prepare to make your mark in the world, it's this. Keep yourself open to experience. Dare to dream, dare to be different. Each of you has a poet inside. I am not speaking only about words on the page. As Karl Shapiro said, poetry is a not just a way of saying things, but a way of seeing them. Each of you possesses the poetic faculty, a gift that enables you to intuit, to sense what is genuine and what is bogus, to see through to the essence of a person, an event, a situation. This poetic faculty deserves to be cultivated and nourished; if so, it will serve you well, giving you a special slant on reality, a capacity to understand adversity, to forge new ways of responding to change, to see beauty and opportunity even in the face of hardship.

When I was young, I tried to write poems to get the attention and win the hearts of young women. Unfortunately, these poems opened no doors for me. I had not taken the time to learn the craft or give my full attention to the beloved. Only later did I learn that all good poems, whatever their subject-matter, are love-poems. They speak, first, of our love of the language; then they speak of our love for the things of this world in all their glory and tatters. Ted Hughes described poems, not inaccurately, as urgent communications that have the character of "ragged dirty undated letters from remote battles and weddings."

Tell our current leaders and those who replace them that guns and war are not the answer, that clichés and Band-aid solutions will not save the planet or halt the spread of AIDS. The tools you've acquired and the solutions you are pondering as you emerge from this period of formal study at Royal Roads will produce far-reaching results. Be bold in your pursuit of what is good and what is of genuine human value. I salute your achievements in, and commitment to, justice, environmental stewardship, peace building, leadership, learning, communication, conflict analysis and other diplomatic alternatives. As a poet, I'm honoured to be associated with you, your work and your university.

Together, let us explore the many ways of way of being in love with the creatures and the forms of this earth, for the earth and its atmosphere and its peoples need nothing more, at this point in history, than the loving attention of the poet in each one of you.